The Dark Corners of the Mind

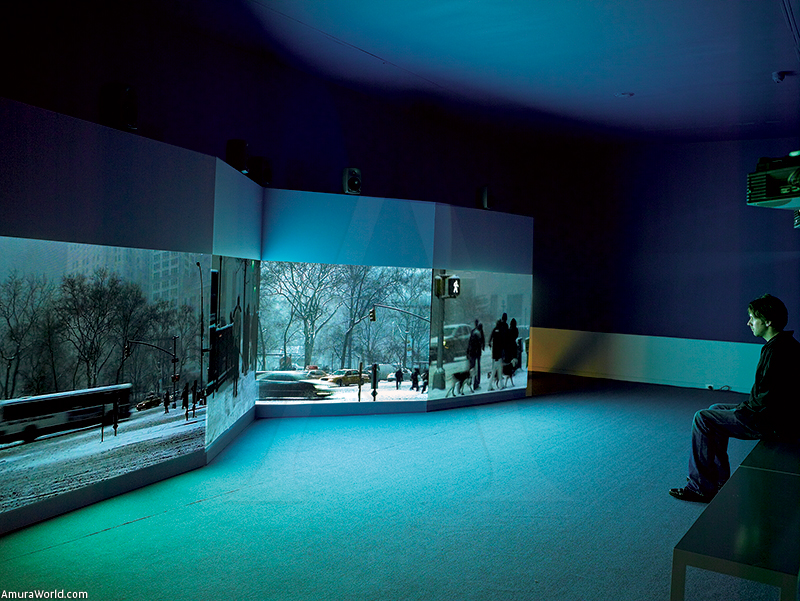

The Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (K21) Museum in Düsseldorf recently opened the Eija-Liisa Ahtila exhibition. The exhibition features a collection of the most outstanding work produced during the artist’s last decades of production. From the mid-1990w, Eija-Liisa Ahtila (Finland, 1959) has created hybrids indistinctly between the worlds of cinema and video. Her video installations have contributed to the creation of narratives that fragment the space-time perception in contemporary art.

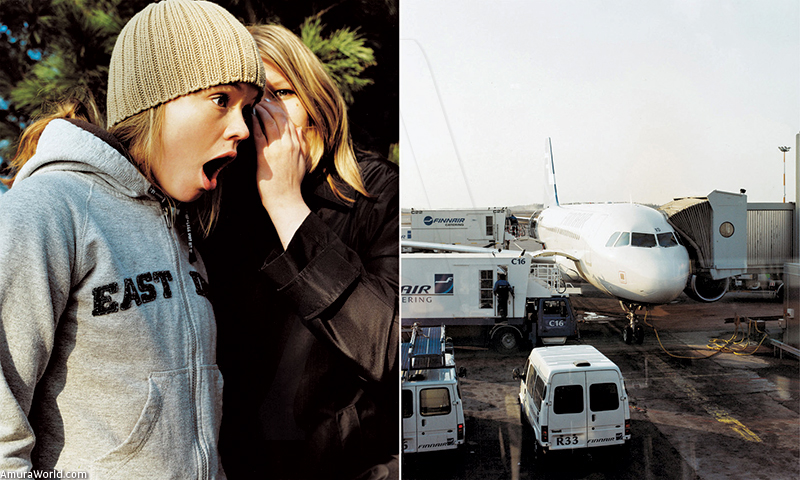

The sample brings together videos such as Me / We, Okay, Gray (1993), If 6 Was 9 (1995-96), Consolation Service (1999), The Present (2001), The House (2002), which is part of the K21 collection, and Where is Where? (2007-08).

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s work weaves fine threads between fiction and documentary, reality and real, psychology and theatrical, spatiality and awareness and text and voice. One thing is certain: ambiguity is a constant factor in Ahtila’s work. The strategies of temporary fragmentation and spatial simultaneity in her work turn our perception into an active agent; into a decipherer.

Ahtila provokes our understanding of reality; challenging it, playing with it. She presents fantastic realities some of which we can identify with. For example, The House, the story of a woman who goes through psychotic episodes forces us to ask ourselves about the ambiguous limits of madness and sanity.

To a certain point, her narrative is documental because it is based on research and interviews with women who have experienced psychotic episodes. In a kind of imitation of the psychotic perception, Ahtila turns to fiction as a representation strategy to allude to that strange and distorted reality from which her characters emerge. We are active witnesses of that perpetual state of psychic disorientation that translates into an alteration of reality and the disintegration of the logical apparatus that represents the world to us. “

I think the living room of my house is breaking down”, says Elisa, the lead character, and continues “It can’t keep things out anymore, can’t preserve its own space. My garden is coming into my living room.” Suddenly a renegotiation of what we understand by reality emerges. A dark aspect of things emerges to expose us to our own strangeness. The real emerges, something that Lacan, with no more tools than language, denominated: the impossible.

Ahtila’s images reveal the mistaken side of the world; its fake dress. But as soon as we see the uncontrollable vertigo that implies the renegotiation of our capacity to interpret the world, the image conjures up harm. On saving ourselves, we think ourselves as relieved from someone else’s untransferable reality.

That we are not ourselves, that we have never been ourselves who have doubted the ontological statute of reality. However, the danger has been indicated Ahtila has delicately touched one of the sore spots of the image and the real. I will briefly quote Clément Rosset from his book Le réél: traite de l’idiotie: “The image serves here to challenge the real, to push it away.

Generally, this function is effective in situations of urgency; in other words, when one finds oneself faced with a reality that, in situations of grave crisis, must be evacuated immediately and displaced by any means possible. The brutality of the event is therefore buffered by the spectacle of its interpretation.” The real disappears at the time of its representation, which always appears slowly.

The House, together with another four videos, belongs to a collection of work called The Present. Together and fictionally, the five videos portray the experiences documented by Ahtila during interviews with psychotic women. It is another work, Scenographer’s Mind (2002), which consists of a series of 18 medium and large-format photographs, which sheds light on the process of the construction of an image as an equivalent to the process of the construction of sense.

This work makes constant reference to The House and we could think that it works as its remnant. But in this case, the fixed image, unlike the moving video image, delicately explores the importance of space in the creation of awareness and in the best of cases, the creation of a sense. In Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s work, space functions as a reflection of the interior world of the characters: a mirror of awareness.

In her work, fantastic realities submerge us in the existential states of her characters by modifying the space and time perception. And it is through these perceptions/reflections that Eija-Liisa touches on extreme situations of life, such as attachment, separation and grief, difficult process of growing up, the encounter with death, encounters with others and above all encounters with oneself and the dark corners of the mind.

Text: Anarela Vargas ± Photo: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen / Nauska*.