A Nobel to Remember the Holocaust

Literature is the recreation of a microcosm where form and style recreate events, experiences, epics.

Sometimes human beings are able to exteriorize issues that, precisely because they surpass the imaginable, test the capacity of language to do its job while preventing oblivion.

Even though it’s been 75 years since it came to an end, the Holocaust remains one of the greatest pending crimes of humanity. More so during these convoluted times where a discurse of intolerance, racism and rejection of the other prevails, as Erich Fromm has mentioned in his essays.

The anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945 is commemorated each year on January 27. Even though the United Nations (UN) postponed its celebration until 2005, it’s even more surprising that the Swedish Academy waited until well into the 21st century to award the Nobel Prize to a survivor.

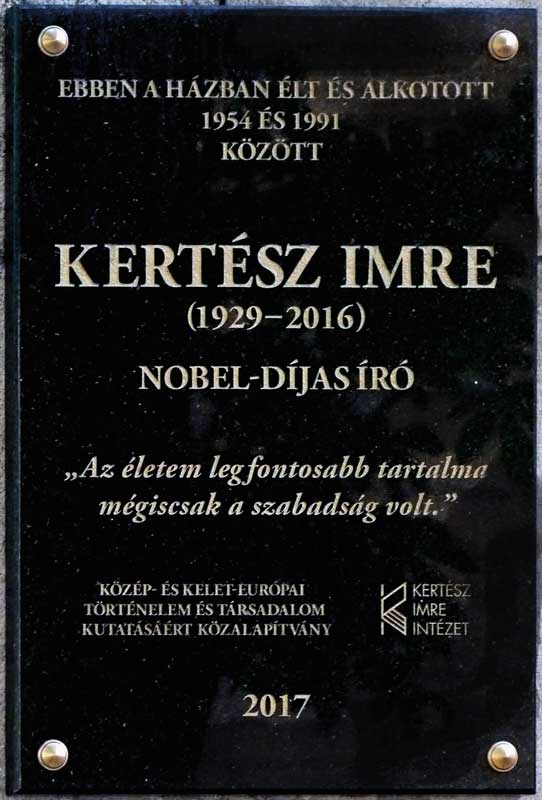

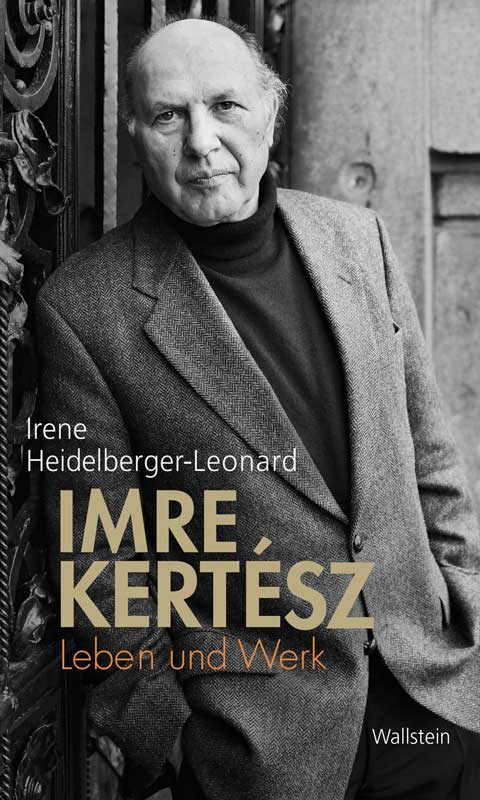

Imre Kertész

(Budapest, 1929-2016)

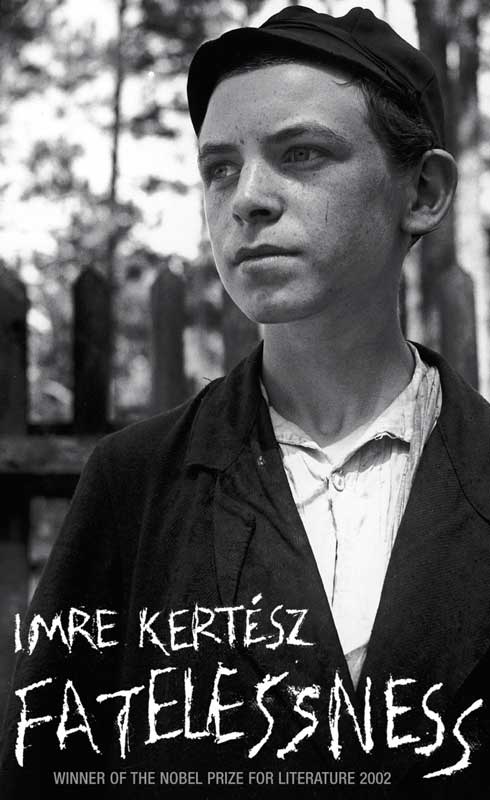

The young Hungarian deportee, who was barely 15 years old, was kind enough to present, in a graphic and innocent way, the brutality of the Nazi soldiers before the massacre of millions of Jews: “A tall man with an imposing appearance appeared then, approaching us from an adjoining building. He wore high boots and a tight uniform, with golden stars and a leather belt that diagonally crossed his chest. In one hand he carried a small whip like the ones used for riding, with which he continuously beat his shiny patent leather boots. A minute later, while we waited, motionless and formed in rows, I found he was a handsome, strong and athletic man. It reminded me of the heroes in movies: attractive, with virile features and a thin brown mustache, shaved impeccably in fashion, and which looked great in the middle of his tanned face.”

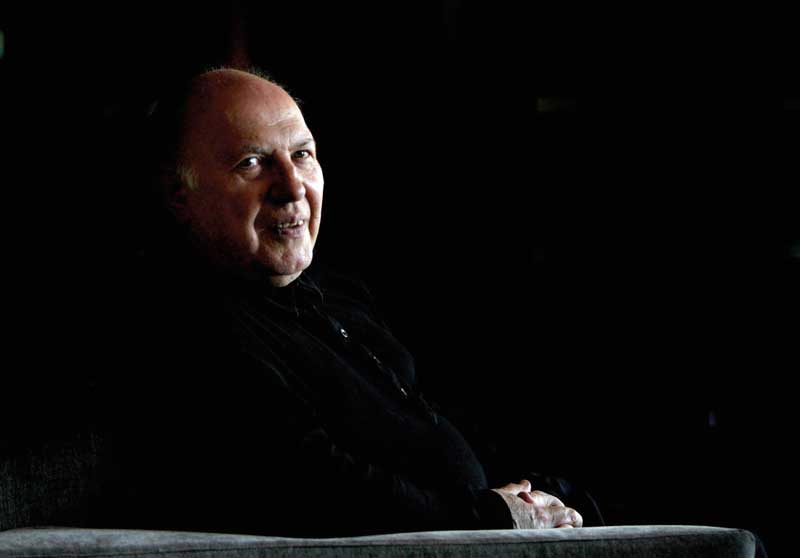

The narrator and essayist who shared the experience of extermination through his works Fatelessness, Kaddish for an Unborn Child and Moments of Silence While the Execution Squad Reloads, was faced with two paradoxes when he gained recognition. First, the man who was deported in 1944, wondered while in Sweden why he had been awarded the Nobel Prize, given the growing presence of authoritarianism in Europe. However, the specialists saw the need to recreate the horror of intolerance and hatred of other peoples in this fact, similarly to what is currently happening in the European Union. The second paradox was that Kertész died on March 31, 2016, the same day the UN reminded the European Union that out of the 22,000 refugees it had accepted to host in 2015, only 4,500 had arrived at its destination.

Fighting Oblivion

The Nobel Prize for Hungarian Literature passed away at the age of 86 in his native Budapest. Some say his work Fatelessness, which came to light in 1975, took 13 years to write. The man says that when he returned to Hungary, not only did he find his parents’ apartment occupied by strangers, but he realized that he was completely alone—his entire family had been swallowed by the Nazi machinery.

The writer was aware that literature went beyond words. “The essence of my work is to convey what happened to a spiritual dimension. To remain in the conscience, although now I see it with less optimism. The Holocaust is the universal collapse of all the values of civilization and society cannot allow it to ever happen again. The economic crisis gave way to the rise of Hitler to power. Therefore, alarms should be blaring now. But they make no sound. Which means that the Holocaust is not present in the conscience of European politicians,” he warned.

Kertész’s work is an immense recount of our capacity for survival; of a moral recomposition based on the knowledge that any horror is possible, before which, we must stand tall with no fear: “How must we write? (...) Stendhal, in a prologue, draws attention to his ‘few and select readers’, where a surprising twist stands out in the phrase: ‘Try to live your life without hate or fear’. From whom did I learn more? I think from Thomas Mann (I learned the audacity and the position of the writer, the diligence and dignity, and last but not least: culture), and Camus as well (I learned to cling impeccably to a single subject as the only possibility), all art also leads to a subject to rediscover. “

“My work is a form of commitment to myself, to memory and to humanity.”

- Imre Kertész

Text: Mario Vazquez ± Photo: la croix / wpfd / casas del libro / The Washington post / DR / libpbr jamsa / amazon / vbutchen