Breve repaso histórico de la navegación mercante

When did humans begin to be transported by sea? We don´t know. But with a little bit of imagination we can recreate that moment. Let’s go back in time to the Upper Paleolithic. A Cro-Magnon is on the bank of a river, probably fishing. Suddenly he sees, passing in front of him, a tree trunk floating, washed away. It draws his attention because he has never seen anything like that before. He knows that the trunks are heavy and therefore doesn´t understand why it does not sink in water. Finally, the trunk moves on and also our Cro-Magnon. Years later, another of our ancestors observes a similar scene, but this time the trunk is stuck between two rocks. Bolder than the other one, he walks over to inspect and climb on it. Immediately, the trunk dislodges and continues its path on water, with a more than terrified man on it. Voila! Navigation is born. Maybe it didn´t happen quite like this, but it sounds good.

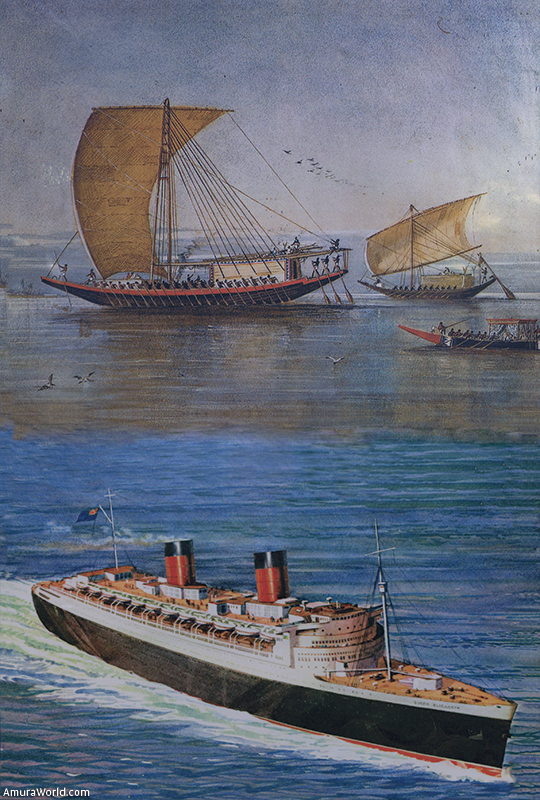

Undoubtedly, navigation was born before the first cities. The oldest known canoe was found in Pesee, Netherlands, and is more than 8,000 years old, which indicates that when humans began to settle in large villages on the banks of rivers, they already knew and dominated this art. Had it not been so, what would’ve been the point of living near water? This idea is strengthened when we analyze the Sumerian culture, the oldest one known, and realize that their ships roamed the Tigris and Euphrates connecting large cities and transporting their goods to trade between them - It was probably them who invented sails to harness the power of wind. The same can be noted in the other major early cultures: China, India, Egypt and Mesoamerica.

However, the mariners per excellence of antiquity were the Phoenicians. These brave sailors cemented their prosperity in trade, not war. With their large ships they carried up to 100 tons of merchandise throughout the Mediterranean, as well as the Atlantic and Indian oceans. It is even said that they were the first to circle around Africa, and even their possible arrival to America is speculated, centuries before Columbus. With them it became clear that traders were essential for the discovery of new lands, because with their ships roaming all coasts, they expanded the geographical knowledge of humanity and contacted distant and different cultures.

After them, in the Mediterranean world, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans would come, and they would raise great empires based on trade. When Rome became the most powerful city in the Mediterranean, merchant ships from Europe, Asia and Africa arrived at the port of Ostia full of exotic products to a market in constant growth.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the world, Chinese and Japanese imposed their dominance in Asian trade. Particularly, the powerful Chinese empire would build the largest ships of antiquity, only surpassed by Europeans until the eighteenth century. In the Mesoamerican world things they were not going as good. These peoples failed to advance beyond simple canoes, which did not prevent them to sail along the coastlines, commercially connecting places as remote as the Caribbean with the Andean world. In these latitudes, maritime trade was also stimulating economic development of indigenous peoples.

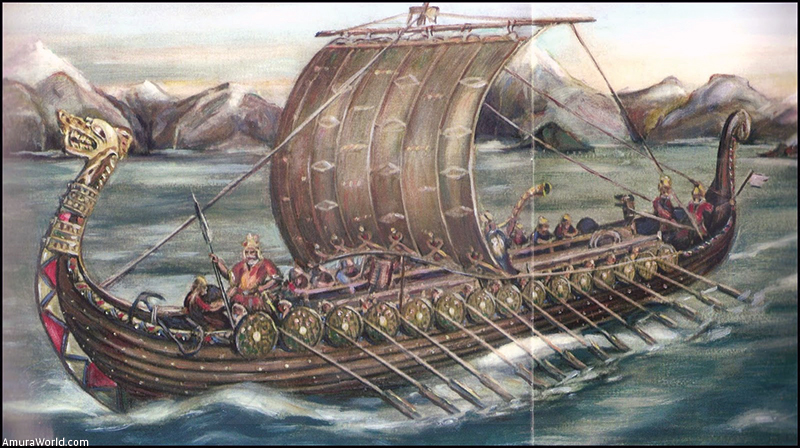

With the fall of Rome, it will be the Byzantines (Romans also), whom will take control of the Mediterranean commerce, at least for a while, until Arabs, Venetians, Genoese and Catalan take away the privilege. Up north, meanwhile, the Vikings will give a new impetus to maritime development. Contrary to what is often thought of them, these intrepid sailors were not only fierce raiders of defenseless towns, but they actually preferred trading over looting, carrying their goods on board the Knorr, their merchant vessels. During the High Middle Age they will undoubtedly be the best sailors in the world, allowing them to be the first Europeans to arrive, this time in documented form, to America.

When the Vikings disappeared, their place in commerce in northern Europe was taken by the cities of the Hanseatic League, led by Lübeck, Germany, whose economic power, derived from the maritime trade, became significant during the late Middle Age.

With the end of the Middle Age and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans, Europeans will be forced to leave their borders, to recover the spice trade from China through the so-called Silk Road. These new explorations would remain in the hands of Portuguese and Spanish from the mid-fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries. The invention of the Caravel, a type of ship capable of open-ocean sailing, allowed Columbus to successfully carry out the journey that led Europeans to establish a permanent contact with the American world and allowed the two Iberian countries to become the first ones with an overseas empire.

After the Iberians, it was the Dutch and the French who started their own naval development, which led their ships to set sail for North America, Asia and Africa during the seventeenth century. By the hand of their merchant marine, with increasingly larger and more powerful ships, over the following centuries the Europeans took over the globe, carrying their flags and their products to the most remote corners, while China and Japan, their most powerful rivals in Asia, decided to withdraw from the world, breaking their trade links and ending their merchant development.

In this journey, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries certainly belong to Great Britain whom, thanks to its merchant fleet, built the largest empire that’s ever been known. At the same time, the British put science at the service of their commercial development. Before naval clocks (chronometers), it was very difficult to navigate for long distances with any accuracy. However, the position of a ship at sea could be determined with reasonable accuracy if a navigator could refer to a clock that lost or gained less than about 10 seconds per day.

The marine chronometer keeps the time of a fixed location, allowing mariners to determine longitude by comparing the local high noon to the clock. The British government offered a large prize of £20,000, equivalent to millions of pounds today, for anyone who could determine longitude accurately. The reward was eventually claimed in 1761 by a simple carpenter from Yorkshire, John Harrison.

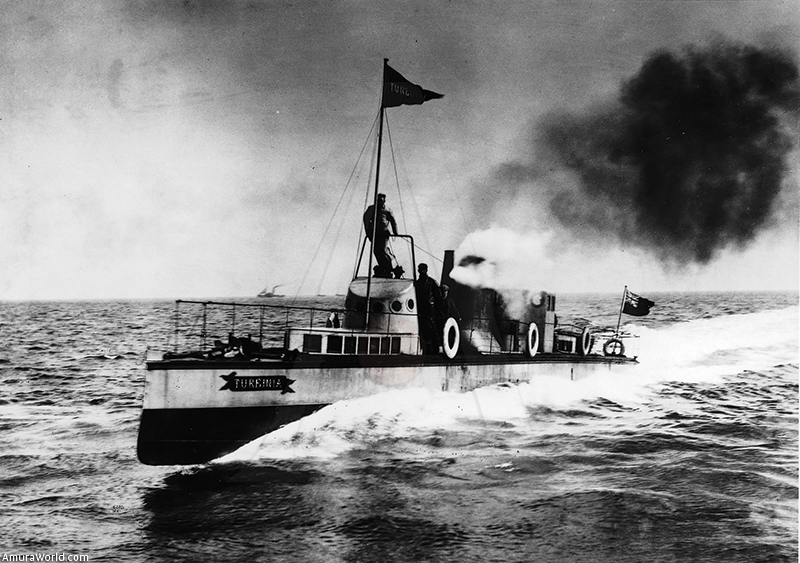

Another big step will be the invention - in the eighteenth century - of the steam engine, which will soon be perfected to be placed on ships. With this, the nineteenth century will see the emergence of larger and faster ships that will close the gap significantly. With steam, wind it does not matter, because ships can move independently of it even in calmer waters. This, of course, also marked the end of the suffering rowers. Only the Clipper, a narrow and elongated sailing ship, which made it very fast, managed to survive until the early twentieth century.

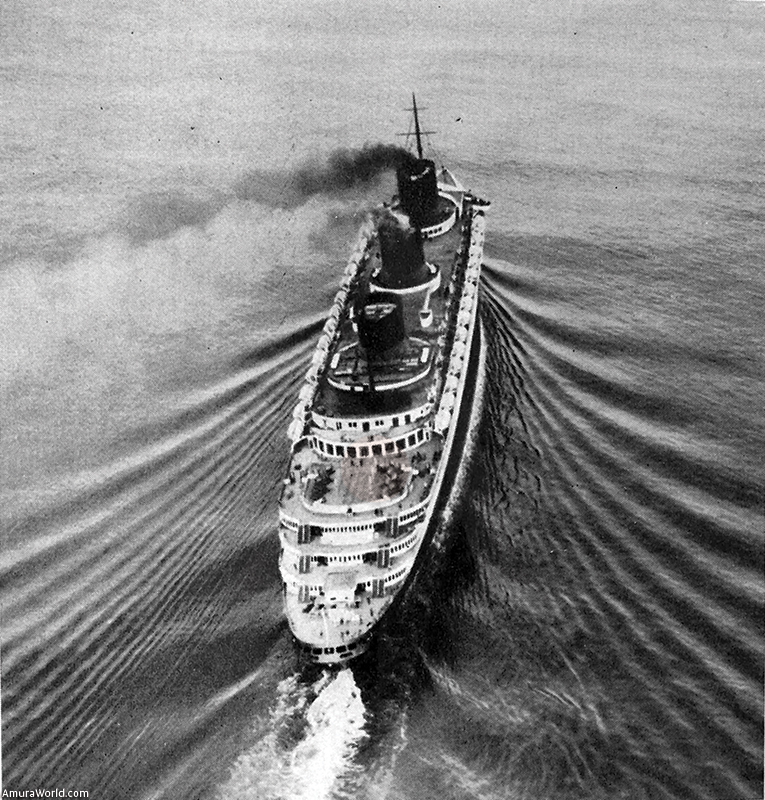

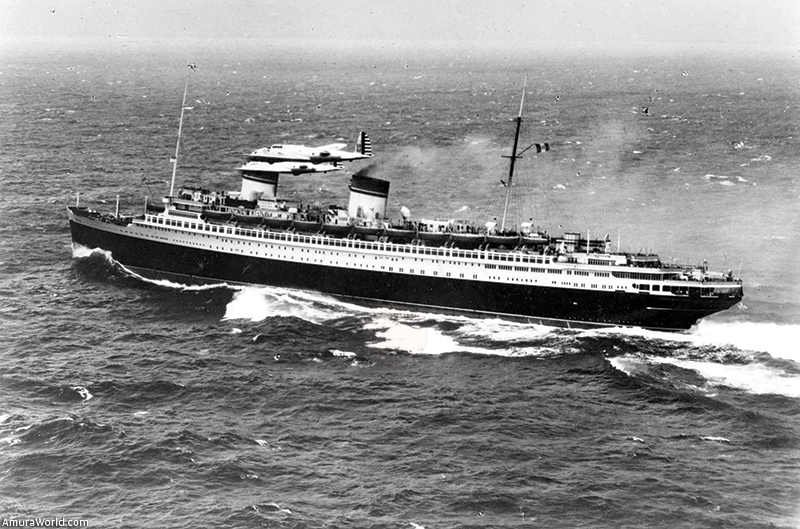

In 1939, at the start of World War II, the world merchant fleet consisted of 30,966 vessels with a total of 68,477,243 tons of registration. The giants of the sea, 170 vessels of over 15,000 tons, numbered themselves alone more than 4 million tons of registration. The largest were the Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary, British; the Normandie, French; the Rex, Italian; and the Europe, German.

World War II highlighted the importance of having a large merchant fleet. Britain managed to stay in the war, despite being subjected to a harsh blockade by Germany, thanks to supplies that arrived by sea from the United States, whether on their own or in American merchant vessels. Realizing this, the German Navy, both underwater and the surface, turned its energies to hunt down and sink the greatest possible number of merchant ships. The numbers are simply terrifying: to 1943, 5,241 ships had sunk, most of them merchants (including six Mexican vessels). In this situation, the United States launched the most ambitious plan in shipbuilding history: the Liberty ships. Using new designs and building methods, they managed to create up to three ships a day, which easily compensated the losses inflicted by the German U-Boats.

Currently, maritime transportation is vital for the world’s economy, because it is responsible for 90% of trading of fuels, foodstuffs and basic materials, essential for modern life. With ever bigger and more capable ships, the future of the merchant marine is guaranteed.

Text: ± Photo: LSMF / National Geographic / ALCANTE PRESS / BP / MY STORY