This marvelous sparkling wine, called by some “the king of white wines,” is made with grapes that grow exclusively in vineyards located in the Champagne region of northern France. Champagne was the first wine-growing region to be delimited by a law enacted in 1927, that restricted it to a 35 000-hectare district made up of 237 “crus” or parcels of vineyards.

At the end of the 17th century, Dom Perignon, a Benedictine monk from the Haut Villers Abby, was the first to mix varietals and vintages to produce magnificent, unique wines. He is attributed with the discovery of the “champenoise” method needed to produce these fine brews.

Three grapes or varieties are authorized for making champagne: the white, called “Chardonnay,” gives freshness, elegance, subtlety and verve; and two reds “Pinot Noir” that gives body, strength and persistence, and “Pinot Meunier,” that complements the other two varieties to produce a full-bodied wine with a good aroma.

Most champagne manufacturing starts out with a mixture of these three varieties, although it can also be made with just one kind of grape. If it is white, the champagne is called “Blanc de Blancs,” and if it is a coupage, or mixed with red grapes, it is called “Blanc de Noir.”

The process begins with the grape harvest at the end of August or the beginning of September, depending on the climate. Champagne is one of the few regions of the world that is still not totally mechanized. The harvesters collect the grapes in small baskets that hold no more than 3 kg. They hand the baskets over to the loaders who transfer the bunches of grapes to larger baskets, holding 40 kg, thereby preventing the grapes from getting squeezed and starting to ferment.

The pressing takes place, delicately and gradually, in pneumatic presses, in order to guarantee that only the best must or juices are extracted. It is important to take special care with the red grapes, since the skin or peel can have an irreversible affect on the color of the juice.

Fermentation, like the wine harvesting and pressing, is done separately. The must obtained when the grapes are pressed is left to repose in stainless steel vats. The juices that will be fermented are clarified in the vats and the yeasts transform the must into wine. This is the stage when the wine acquires its freshness, smoothness and roundness. Next, the sediment is separated from the wine, leaving a tranquil wine, that is to say, with no bubbles.

In November or December, the enologist or cellar master tastes and classifies the wines to make the mixture. The When there has been an exceptional harvest, the cellar master may decide to create a year or millésime, made up exclusively of wines of a particular year.

Bottling: The wine mixtures are bottled and a liqueur composed of sugar and yeasts is added. Then it is closed temporarily with a screw top cap. While the wine ages, the yeasts, that produced the effervescence with carbonic gas, free aromatic substances. This second fermentation, which is used exclusively for champagne, is the key to its development.

Current regulations require a vintage or period of reposing of 15 months for no millésime wines and three years after harvesting for millésimes. When the latter have reached maturity, the sediment that forms during vintaging in the bottle must be separated through a process known as turning or remuage.

Next comes the degüelle. The neck of the bottle is frozen in a tub filled with a -30° C saline solution in order to form an ice floe that contains the sediment. Afterwards, the bottle is uncapped and the ice floe is ejected by pressure.

Once this process is completed comes dosification, the final touch in champagne manufacturing. The cellar master decides on the type of expedition liqueur (composed of reserve wines and sugar) that are to be added, depending on the kind of champagne he wants to make.

Distinguishing good champagne

Wine tasters classify white champagnes as wines that vary from pale yellow to golden yellows, depending on their vintage and date of harvest. Salmon, grey and onionskin are prevalent in the rosés. The pearls or bubbles can rise from the base of the glass in continuous threads or separately, depending on the quality. The smaller the bubbles, the finer the champagne.

It is advisable to consume a no millèsime champagne (no vintage date) during the two years after it has been put on the market, and a millèsime an average of ten years after the vintage date.

To the nose, these wines are associated with the subtle aromas of toast, citrus fruits (lemon, grapefruit and lime), green apples with a touch of flowers in the whites The rosés contain fresh hints of red fruits, like plums, strawberries, currants, and the wild aromas of undergrowth. Some demi sec champagnes (slightly sweet) are characterized by soft aromas with hints of dried fruits, figs, apricots and honey.

To accompany champagne

Champagne is a very versatile wine that goes with appetizers, cheeses, white or red meats, pastas, fish, shellfish and desserts. If you want to combine it with Mexican food, a good mole poblano with a glass of champagne is an excellent option, because it allows you to enjoy the freshness, subtlety and fine bubbles that refresh the palate and generate a perfect balance.

Ideal serving temperature: Ranges between 5 and 10° C, depending on the type of champagne you are enjoying.

|

Laurenti Grande Cuvée Rosé |

|

Aperitif, to accompany Oriental-style cuisine and apple desserts. |

|

Laurenti Grande Cuvée Tradition |

|

Especially good with duck and prawns. |

|

Laurenti Grande Cuvée |

|

Perfect with chicken and wild mushroom sauces. |

|

Möet & Chandon Brut Imperial |

|

A fine choice for all types of strong-flavored foods. |

|

Möet & Chandon Brut Rosé |

|

Perfect with hors d’oeuvres and dishes made with lamb, thyme, tomato, eggplant and olives. |

|

Möet & Chandon, Dry and Nectar Imperial |

|

Ideal to accompany foie gras, blue cheeses and desserts made with peaches, dried fruits and nuts. |

|

Möet & Chandon Reserve Imperial |

|

Grilled or charcoal-broiled meats, sweet onions and oyster mushrooms. |

|

Nicolas Feuillate, Brut Rosé Vintage |

|

Delicious as an aperitif and also combines very well with desserts made with red fruits. |

|

Pommery Brut Rosé |

|

White meat or desserts made with red fruits. |

|

Taittinger Brut Reserve |

|

Ideal with white meats, prawns and mushroom quiche. |

|

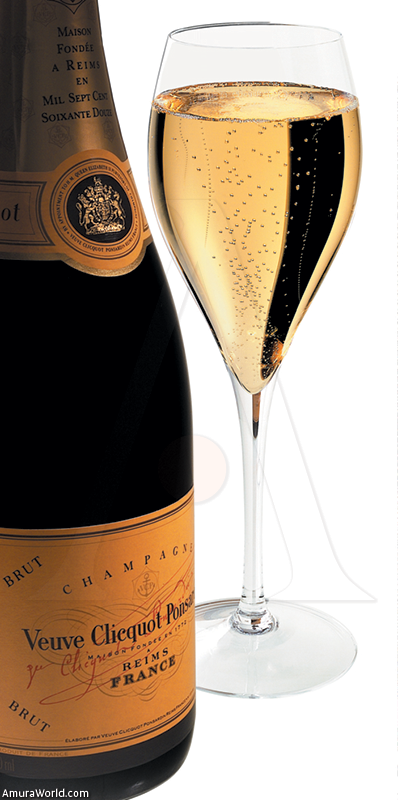

Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin Brut |

|

Lobster and prawns. |

Text: Sommelier Georgina Estrada Gil, Secretaria General, Asociación Mexicana de Sommeliers ± Photo: Moët Chandon