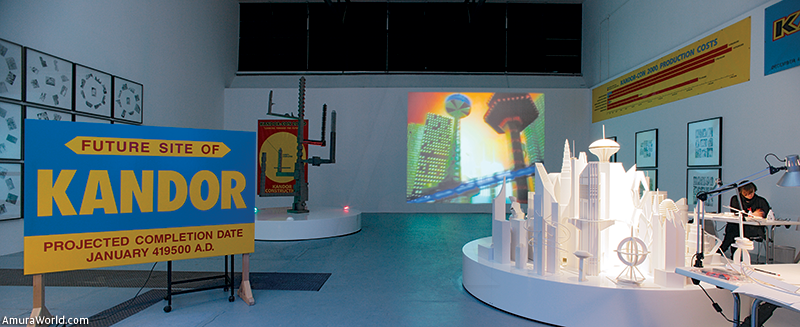

Dreamland was at the Grande Galerie at Centre Pompidou from 5 May to 9 August 2010, the exhibition Dreamlands considered for the first time the question of how World’s Fairs, international exhibitions, theme parks and kindred institutions have influenced ideas about the city and the way it is used. Duplicating and reduplicating reality through the creation of replicas, embracing an aesthetic of accumulation and collage that is often close to kitsch, these self-enclosed parallel worlds have frequently afforded inspiration to the artistic, architectural and urbanistic practices of the twentieth century, and may even be said to have served as models for certain contemporary constructions.

This multidisciplinary exhibition brought together more than 300 works: modern and contemporary art, architecture, films and documents drawn from numerous public and private collections. Designed as an experience both playful and educational, it will offer the first comprehensive exploration of its theme, inviting visitors to think about how the city is imagined and how this imagination finds expression in concrete projects.

World’s Fairs, contemporary theme parks, the Las Vegas of the 1950s and ‘60s, twenty-first-century Dubai : all these have helped bring about a profound transformation in our relation to the world, our conceptions of geography, time and history, our ideas about the original and the reproduction, about art and non-art.

The dreamlands of the leisure society have shaped the imagination, nourishing both utopian fantasies and artistic productions. But they have also become realities: the pastiche, the copy, the artificial and the fictive have become facts of the environment in which real life is led, and they serve as models for understanding and planning the social life, blurring the boundaries between imagination and reality.

From Salvador Dali’s Dream of Venus pavilion for the New York World’s Fair of 1939 to such manifestoes as Venturi and Brown’s Learning from Las Vegas and Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York, the sixteen sections of the exhibition trace the history of a complex and problematic relationship.

Embracing ideas of the city as stage-setting or collage, in this exposition a number of recent developments have found inspiration in fantastical versions of the urban first developed in the enclosed spaces of amusement parks and World’s Fairs. The title of this exhibition was a reference to Dreamland, opened at Coney Island, New York, in 1904. Among its attractions, the park included a boat trip on Venetian canals flanked by facades of painted canvas, and a climb in the Swiss mountains. Destroyed by fire in 1911, Dreamland was the pioneer of an architecture of sensation, dream and entertainment that spread throughout the world over the twentieth century.

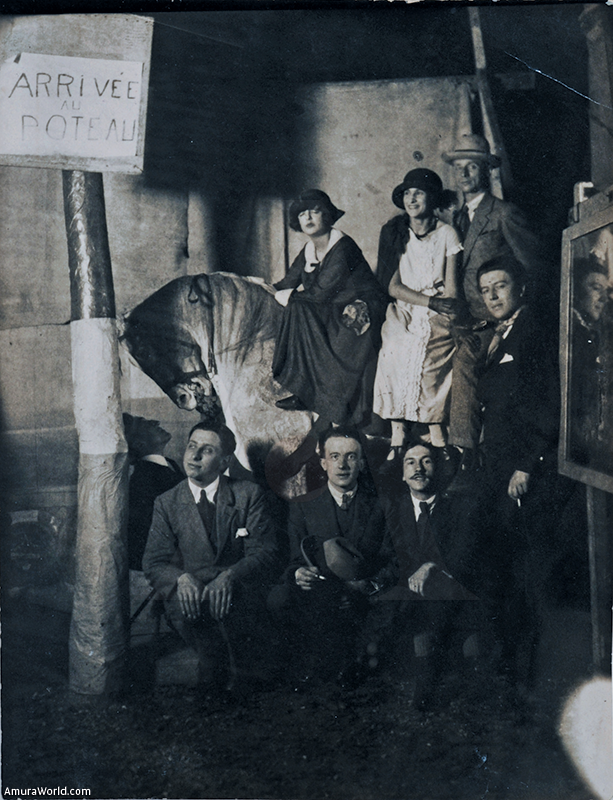

The theme park opened on Coney Island, on the outskirts of New York, in 1904. The elegance of its architecture and the originality of its attractions brought it immediate success and fame across the world. Luna Park opened its gates in Paris in 1909, attracting a wide public, among them artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Fernand Léger and André Breton. The amusement park thus became a point of contact between popular culture and the world of art.

In 1889, in Paris, the Universal Expositions (or World’s Fairs) underwent a change: previously devoted to the display of scientific and technical advances, they now became a vast entertainment. Witness the Eiffel Tower, built for the Paris Exhibition, whose technological modernity serves not utility but the appetite for wonder and spectacle. Within this “great mustering of human progress”, Chinese pagodas stood alongside German half-timbered houses, Khmer temples next to Italian palazzi. This juxtaposition of emblematic national architectures is typical of the self-enclosed world of fantasy that the great international exhibitions would bequeath to the later theme park.

Salvador Dalí designed his Surrealist “Dream of Venus” pavilion for the Amusement Area of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Setting up a deliberate contrast with the geometrical forms of the Fair’s official pavilions, Dali invited his visitors into the Art Nouveau curves and curlicues of the unconscious and its erotic life. The voluptuous world of water nymphs within was suggested by the wave-pattern of the façade, adorned too with myriad protrusions and copies of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Leonardo’s St John the Baptist. Inside, the “dry section” included a nude Venus stretched out on a bed of red satin, clearly embroiled in erotic dreams, while the “wet section” saw an underwater ballet of nymphs staged in a huge aquarium. Anticipating the later Pop artists, Dalí sets his art to swim in the waters of mass culture and the new leisure.

Text: Andrés Ordorica ± Photo: Andreas Gursky, VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn.