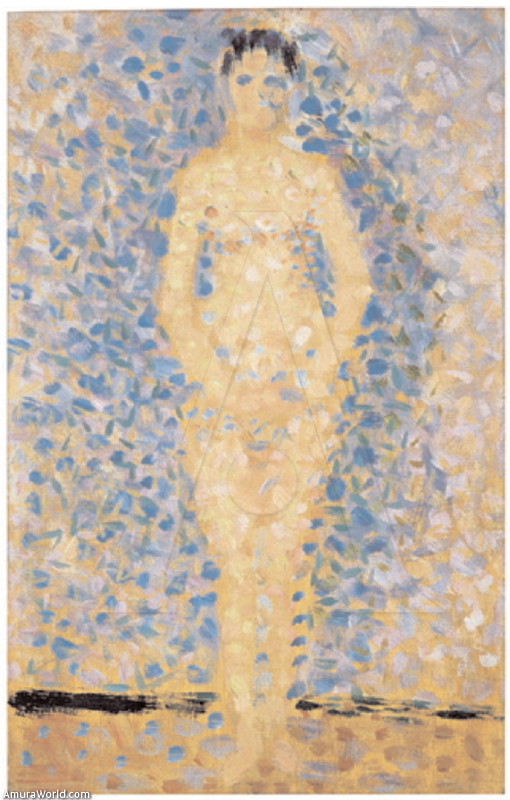

Georges Seurat was bom in 1859 into the bosom of a well off Parisian family. He was one of the main exponents of pointillism. He was a studious of the theories of color and perception available in his time, particularly the doctrine of simultaneous con- trasts of Eugène Chevreul, which completes the process of gradual dissolution of color planes with points of paint that become ever smaller, which was pioneered by the Impressionists. However, the chromatic decisions in Seurat’s work are not a spontaneous and instinctive movement as in Impressionism, but instead are crystallized a rational fact with scientific basis. The tiny juxtaposed dots of multicolored paint allow the eye of the viewer to blend colors optically, rather than having the colors blended on the canvas or pre-blended as a material pigment. Seurat died in 1891 at 31 years of age days after having contracted a respiratory disease.

Seurat’s art is of capital importance although the history of art has dismissed them. The study that he conducted on dramatics and light and dark is not represented in his paintings. This painting style is rigid, severe and straight like the Cartesian philosophy to which he belonged. His paintings seem to be inhabited by automatons or mannequins. Despite his pointillism technique, his compositions are lineal and lack of mystery, flow and life.

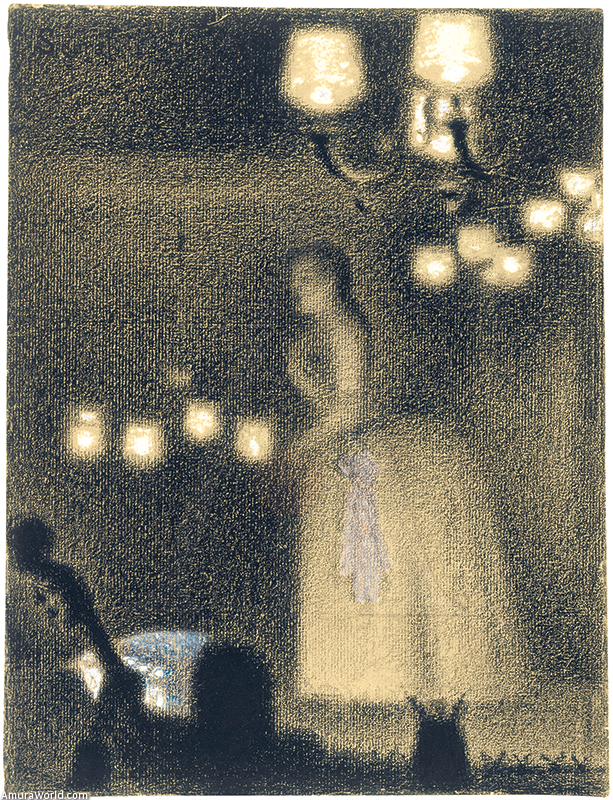

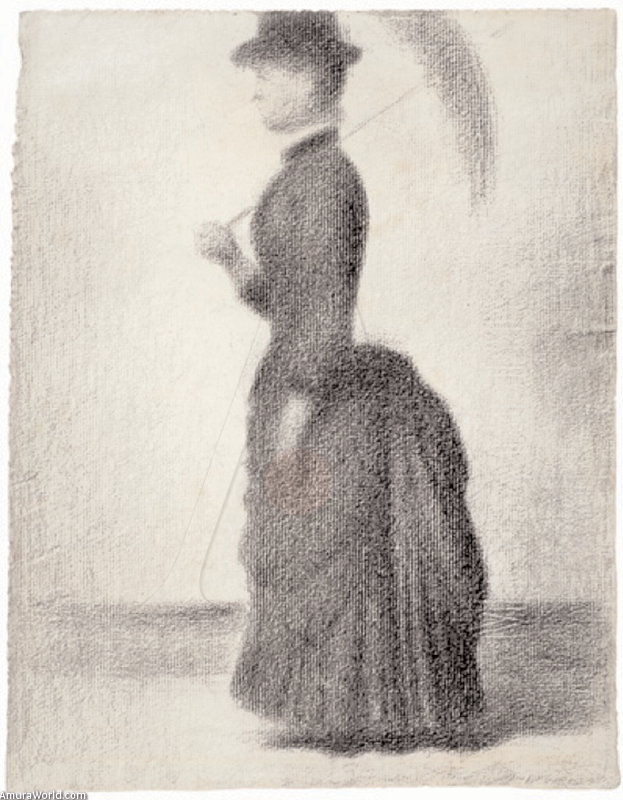

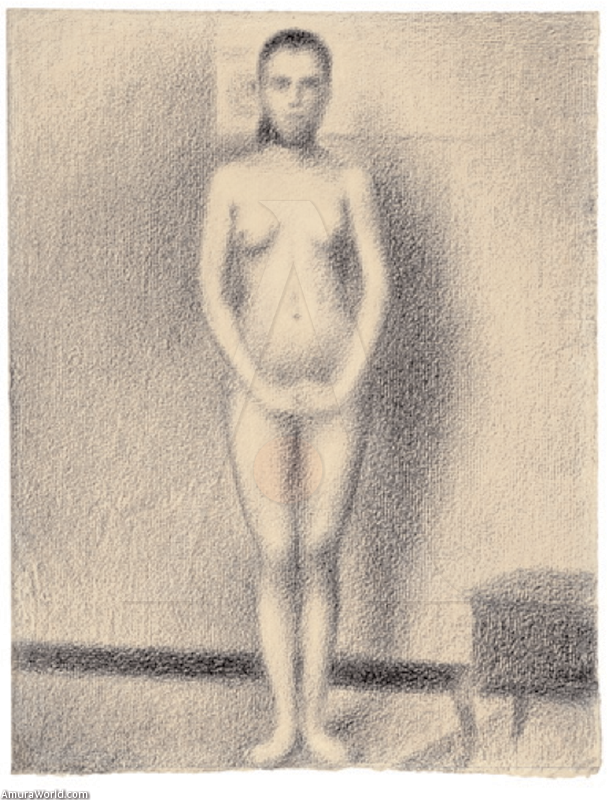

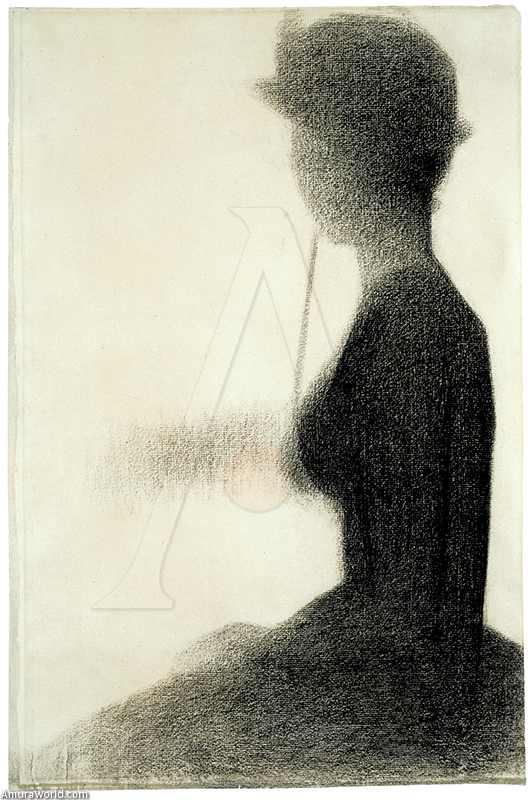

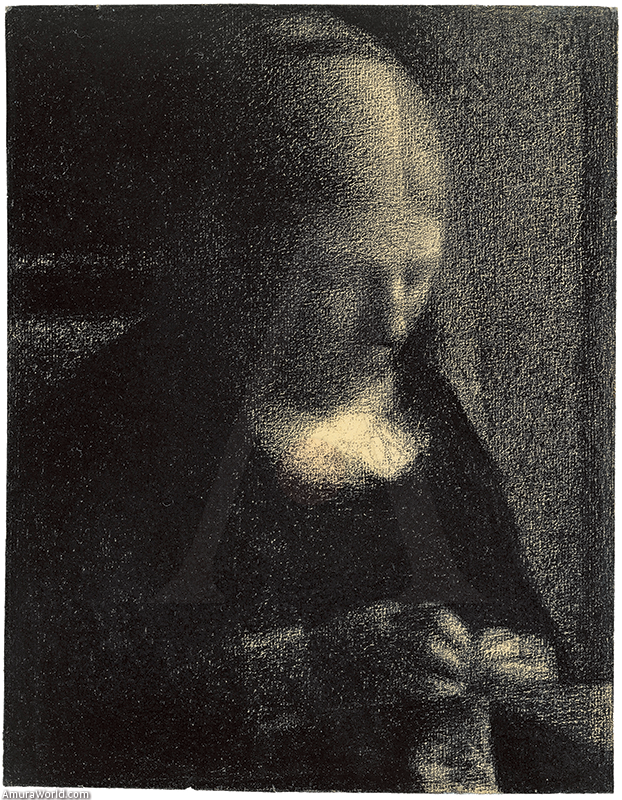

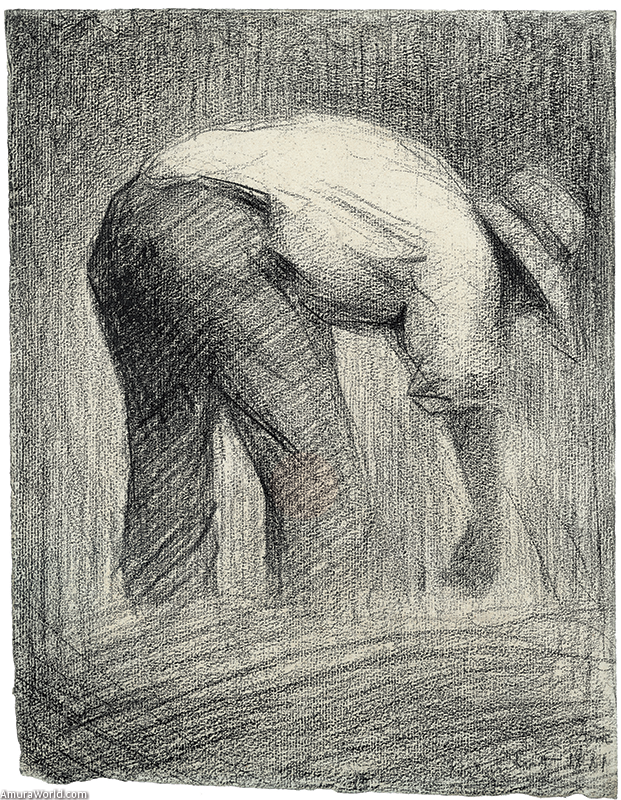

In contrast, his drawings are vaporous like smoke. It is free but dense, difficult to breathe. He rarely used line, his figures march towards the process of their own disintegration or rather they dissolve and can never be differentiated from the background. They always hesitate in becoming geometric figures due to their abstraction, lack of particularity or detail. In this sense, they are always on one side of life always combating their own representation Portrayed to not represent the tiny peculiarities of individual's faces but instead the generic burden of the social players who abound the Parisian city in its painful transformation into a metropolis. We meet the rag and bone man and the wheat cutters, the opera singer, the bourgeoisie lady in a hat. the working class, the peasant and the city dweller. The same thing happens contrast of the spectacle of Paris both sides of its walls: the forced cohabitation of the suburbs and the country landscape. His drawing portrays the aggressive metropolis that was Paris of the 19th century in its project of modernization and its agenda of healing, urbanization and industrialization.

Following the law of contrasts, he creates a state of permanent friction between the materials. The layers of crayon one over the other, creating an atmosphere that radiates light and graduates dark by dispersing and concentrating its density. The solitary characters, involved in their work are the result of the permeable aesthetic of all Seurat’s work; the aesthetic of silence.

There is a mutism in the atmospheric fields of his drawings. His anonymous subjects lack facial features and are always in danger of becoming a pure form or decorated in the background. The darkness of their faces seems to be continually dissolving, veiled over them. As in the case of Embroidery (1882- 83). a portrait of the artist’s mother sewing. This silence of daily life is shared with Johannes Vermeer: two greats of light, silence and the daily grind.

In Birth of the tragedy, written in 1872, Nietzsche, talks of Apollo and Dionysius as the great artistic forces that face each other. On the one hand, the Appollan instinct is a principle of representation and individua- tion A dream-like state that watches over life turning the terrible into the beautiful. And on the other hand, the Dionysian instinct as an non-figurative force that breaks the principle of individuation and flooded everything with the same material returning to the sludge from which life emerges, returning to the origi- nal indistinction Dionysius is the god of drunkenness, the unity of all things, the suppression between the limits of the finite and the infinite.

The dramatics of light and dark of Seurat incar- nate these two principles of the Nietzschean aesthetic. On the one hand, the atmospheric veil of the representation in his drawings, which invites the glance to open the curtain and discover the object, but on the other, this same veil is transformed into an ethereal and disturbing miasma that submerges background and figure into the terrain of what can- not be represented.

Text: Anarela Vargas ± Photo: Cortesía de MOMA