A pedagogic legacy for film

Without a doubt, film is a reflection of the culture of any given country, and Russia is no exception, for we are talking about a country with one of the largest ups-and-downs as far as politics and society are concerned.

Making a brief recap, Russia lived through a monarchy during the empire of the tsars from 1721, up until 1917, when it became the first socialist country after the October Revolution, which in turn became the United Socialist Soviet Republic, until a restructuration is achieved by way of the Perestroika. In 1991, it becomes the Russian Federation.

These political changes are contrasting: to pass through the empire of the tsars, to a socialist republic highly concentrated in Moscow, to a semi-presidential federation in the largest country on our terrestrial landmasses, it no small feat.

And film is no exception. All these changes have molded the form in which Russian filmmakers and actors have understood, executed, and shared their artistic vision, one that is reflected up on the screen.

Russian cinema began shortly before 1910, with the photographer Alexandr Drankov, but it wasn’t until 1925 when it stopped the world’s spotlights by the hand of the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein with “Battleship Potemkin,” in which Sergei used the montage technique imposed by Gardin in 1919.

“Battleship Potemkin” (1925) is, without a doubt, one of the most iconic and representative films of Russian cinema, and one of the most cherished films of international cinema to this day. Sergei Eisenstein used the montage technique to represent the staircase of Odessa, one of the most famous scenes in cinematography.

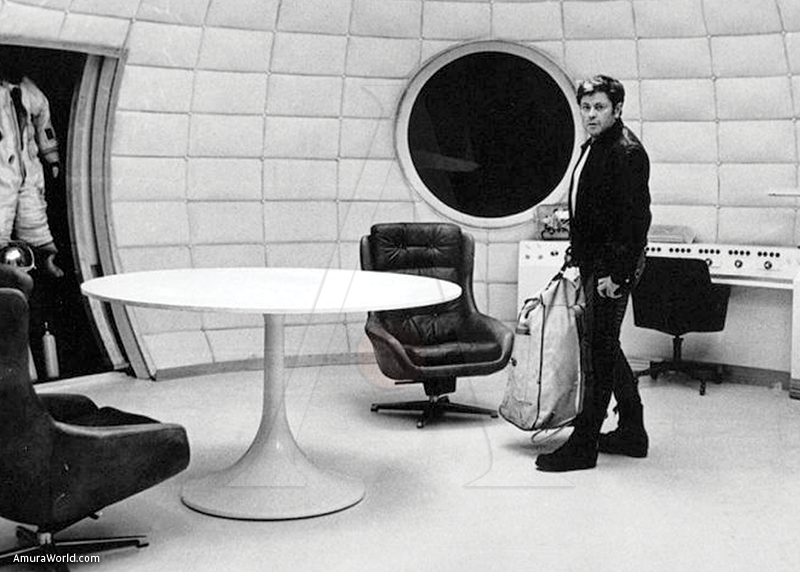

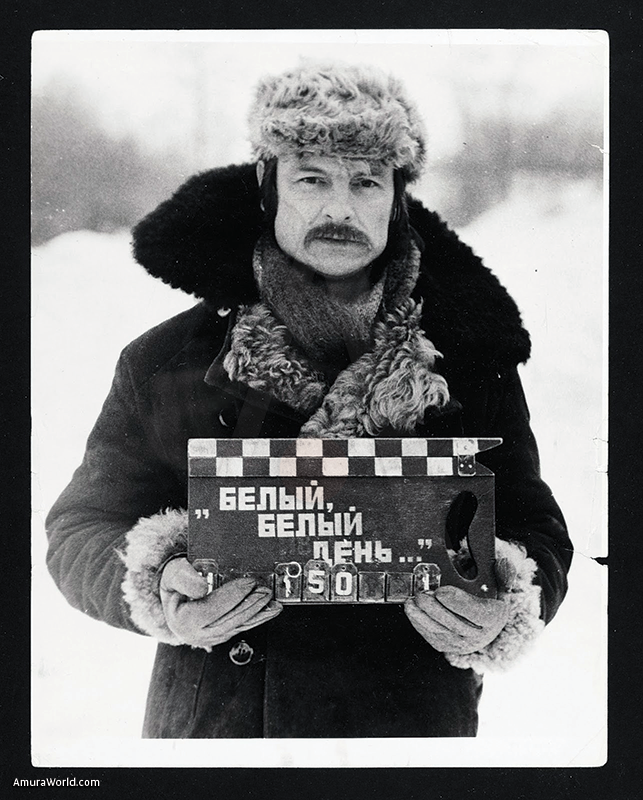

Another pioneer, and one of the most important Russian filmmakers of the last few years, was Andrei Tarkovsky, who busied himself in projecting futuristic elements, greatly extended longshots, shots that include elements of the landscape and nature, as well as an anxiety for technology; a clear example of this is “Solaris” (1972), whith is sci-fi and futuristic vision of the world, as well as “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962), which relates the story of a child spy during the Second World War.

One of the most quotable sayings from this Russian artist is: [Directing] “No ‘sequence shot’ has a right to be repeated, as no two personalities are the same. As soon as a ‘staging’ takes places it becomes a sign, a cliché, a concept (as original as it may seem); then all elements – characters, setting, and ambience, becomes ischemic and false.”

Modern acting was born in Moscow

What would be of film without acting, without a discipline that marks the guidelines of how to prepare a character who carries the weight of the story?

The actor is the one who brings the story to life, whose sensibility tells a story on film. As paradoxical as it may sound, acting is not acting, it is not the feigning of emotions.

What the actor least desires the moment a film completes if for the public to say: “The role played by this actor looked overwrought.” On the contrary, when we go to the theater, we want to see flesh-and-blood beings undergoing a real experience.

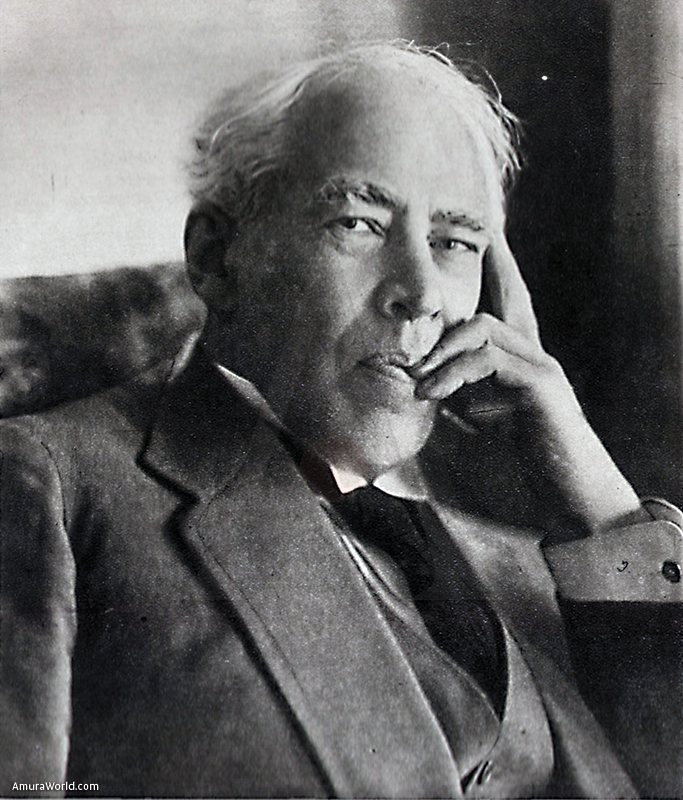

The person who founded the bases for the acting studio as we know it today, the man who dedicated his life to create a method in which a great deal, if not all, theories of acting are derived today, was Constantin Stanislvaski.

Stanislavski distinguished himself by founding, administrating, and directing the Moscow Art Theater in the beginning of the 20th century. During his tenure, he crated the Stanislavski method, which is an approach to the actor’s studio, which, as we have mentioned, is the basis for and modern acting method. This method is based on relaxation, concentration, and the imagination of the actors as the main vehicles to prepare and execute a character.

Stanislavski’s legacy lives forever, since it is impossible for any person who considers themselves as an actor, or as a director, to not dominate the fundamentals that this actor brought forward.

Texto: Juan y Daniel Lecanda ± Photo: WKP/ STANISLAVSKI STUDIES/ MUSGROFO/ openculture/ elgazine/ bp