The architecture of freedom

Zaha Hadid described Iraq during her infancy as a liberal country, and, up until 1985, there used to exist a Ministry for Women. In various interviews, she would tell how her first memory of her vocation dated back to her being six or seven years old; a memory that was linked to the construction of her aunt’s house. She would refer to this moment as one where she could see for the first time, and up-close, the architectural landscape, a sight so magical that instantly fascinated her.

Her father, Mohamed Hadid, a prominent figure in Baghdad, bestowed on her the bests possible education. After concluded her studies at the American University in Beirut, in the field of Mathematics, she began studying architecture at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. This city became the Launchpad and the foundation of her monumental professional career.

“Architecture is the most complex of arts. That’s why it’ so powerful.”

In 1978, she formed part of the Metropolitan Architecture Office (MAO) – an avant-guard architectural group in London – at the same time she was teaching at the Architectural Association. In 1979, she founded Zaha Hadid Architects. On a deeper level, she was perfecting her iron will: a woman, immigrant, Arab, facing a wall of prejudices, yet she turned ever challenge into an opportunity.

For the next 20 years, her projects were considered as fantasies, impossible to be built. Regardless, in 1983, her blueprints and projects were recognized in during a retrospective exhibit at the Architect4ual Association, in London. Since then, they have been showcased in some of the most important museums in the world.

Firmly inclined on becoming a pioneer, Zaha Hadid allowed herself to break all possible rules, shattering reality, reinventing it with her pencil as if it were a magic wand to rid herself of all prejudice, of the finite world of blueprints. She created limitless, impossible, open-minded, defining, and free forms with asymmetric angles; a fusion of all theories and all techniques in order to reconceive architecture as a game that manages to defy the laws of gravity and logic. Standing at the edge of a cliff, only to become, gracefully, one with the sky.

She won contests that ultimately shelved her projects untold times while she pressed on with her day job, creating networks, and collaborating in other fields, and always with the leading figures in the realm of design: scenography, exhibits, jewelry, fashion, objects, furniture – most which soon became cult objects, such as the acrylic coffee table made with liquid glacial resin, which imitates the flowing movement of water, commissioned by David Gil Gallery, and which was nominated for an award in the design during the London Museum of Design, in 2013.

Another highlight of this era was a super yacht prototype, of astonishing design, in a partnership with Blohm and Ross. A digital model can be admired in virtual reality at the Image shop in Selfridges, London.

It wasn’t until 1993, at the age of 43, that she erected her first project: a fire department in an urban complex in Vitra, Germany. Another important step in her career occurred in 2001, with the construction of an innovating jumping trampoline design in Innsbruck, Austria. From there, she built structures in nearly every corner of the globe: urban, cultural, educational, medical, leisure, and industrial structures, as well as housing projects, office buildings, residential homes, towers, sustainable structures, transport hubs, and more under the authority of her own firm: Zaha Hadid Architects.

For fourteen years, she developed a vertiginous career, dedicated through and through to the passion in her life. She did not marry, nor had any children. It was simply a life of great achievement and properly earned prizes, hundreds of which can be named. In 2004, she was the first woman to be the sole recipient of the Pritzker prize. Furthermore, she was named a Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for her services to architecture, granted an honorary Doctorate degree from the London University of Arts, and formed part of the Encyclopedia Britannica editorial group, amongst many other.

A month after being awarded the Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects – the first woman to receive this prize – she was at the height of her professional career. Yet, on the 31st of March, 2016, she passed away, and paved the way for a legend whose dimensions are yet to be fully explored and described. She left behind around 36 incomplete projects, some still being constructed, and others on paper, in 21 countries around the world. All will be developed, according a spokesperson at Zaha Hadid Architects.

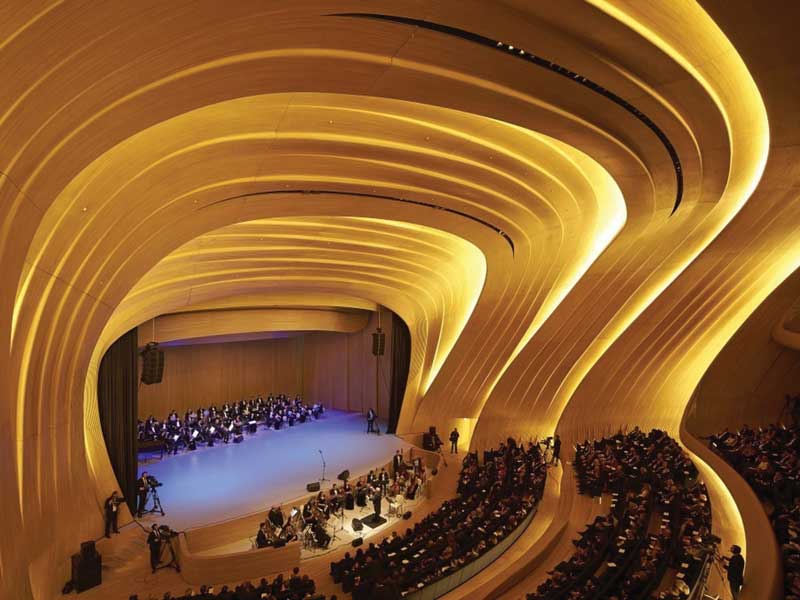

Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku

Opening its doors in 2013, it has rapidly become an obligatory destination for any and all visitors and locals in Baku. It is a staple Zaha Hadid design, one which earned her a commission by the cultural department of the Republic of Azerbaijan in 2007. It was design with the sole intention of establishing an interrelationship between the plaza and the areas that surround it; as unique urban space in Baku. The structure elevates and envelops another public space with numerous conference rooms, a library, museum, three auditoriums featuring shows and content that revolve around the traditional and contemporary art scene, as well as with multiple cultural bonds formed in the region.

Text: Maruchy Behmaras ± Photo: Zaha Hadid Architects / WIRED / © TAWATCHAI PRAKOBKIT / © TANAWAT PONTCHOUR / © ZHI EN HUANG / © TANGDUCMINH / © BEIJING HETUCHUANGY / MTCV / TCHNIVER / SAHARGHAZALE / ART DESIGN / TCHNIVER / SAHARGHAZALE / ART DESIGN / AYT IBIZA / ADTCC / BP / © EQ ROY / © SILVIU MATEI / EESTATIC